A Dream Come True

by Brett Boyd

Okay, so I said there would be no more gun projects! Well, I meant that there would be no more new gun projects. With gunsmithing delays running into the years, it was a pretty safe bet being secure in the knowledge that my backlog of projects “in progress” would probably last me the rest of my life! Now that I’ve got this off my chest, let me bring you up to date.

As a youth I spent many hours perusing the “Museum of Historical Arms”

catalogue dreaming of holding, shooting and perhaps even owning one of the classic guns of yesteryear. These dreams were further animated by other reading material by the likes of Ruark, Whelen and O’Conner. Big game hunts, trophy animals of every sort, nights by an open fire, tales of the hunt and visions of open spaces filled with roaming critters of every sort, such were the images filling my youthful noggin. Somewhere in all those memories, maybe it was the Jack O’Connor era, who knows, that the picture of an American hunter after bear, moose, and elk, armed with a Winchester high wall seemed to incorporate all the romance of the outdoors.

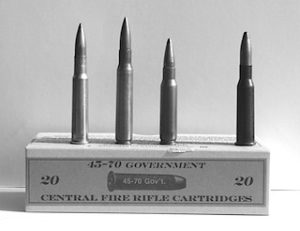

Over the years I have had a fascination with the later models of the Winchester high wall, particularly those chambered for the 30-40 Krag round. As most of you know, this cartridge, originally known as the .30 U.S., was the first smokeless round adopted by the government for use in the venerable Krag Jorgensen bolt rifle of 1892. The introduction of smokeless powders radically changed the equation in terms of velocity and bullet weight. The trend quickly went toward smaller, lighter bullets at velocities approaching three times the speed of the old black powder big bores. Hunters and soldiers alike extolled the virtues of this new technology. Old Teddy Roosevelt [photo below: Teddy with son Kermit] didn’t hurt the cause either with his exploits using the Krag round and the awesome 405 Winchester, albeit in lever action rifles. Someone should have had a talk with him on this final point! We probably would have used the Krag round right up to the .7.62 NATO era had it been rimless in its design. As a matter of fact, loading the 30-40 Krag with modern smokeless powders easily equals its .30-06 replacement.

Winchester was quick to adapt or create new rifles for these potent smokeless cartridges. Fortunately the high wall single shot was plenty strong enough for these new high intensity rounds. Soon Winchester was chambering the high wall for the 30-30, 30-40, 303 British, 32 Special, 33 WCF, 35 WCF, 405 WCF, and even the 30-06, all smokeless rounds which were quickly accepted by sportsmen around the world.

While the new cartridges were well accepted, the era of the repeater was underway and the single shots soon faded, with the last of the Winchester high walls being made around 1920. Not many of these rifles were made in 30-40 but enough survive today as a testament to their reliability and utility as big game rifles. Occasionally one sees a fancy one, all decked out with pistol grip sporter stock and sometimes even with one of the old-style German hunting scopes. I saw one just like this when I was a kid down at Jaegers Sporting Goods in Jenkintown, Pennsylvania. It looked like one old Teddy would have used if he had only had the good sense to use single shots.

Well I’ve certainly taken the circuitous route to lay the groundwork for a project that began almost five years ago. A trip to the South Carolina mountains to meet a “backwoods” gunsmith begins the story. A good friend called me and said he knew a guy living in a cabin with no running water or electricity, who worked part time for cash only at a local machine shop and had an old Winchester single shot he wanted to sell. You just have to follow up on one like this.

After about three hours of driving the last couple of miles on a washed-out dirt road up a mountainside, we parked in front of a 15 by 20 foot rustic cabin. Sure enough a sixty-something old gent came rambling out to greet us. The old feller was pretty deaf and my buddy screamed greetings and introductions. Inside the cabin there was a chest of drawers, a small simple bed, a wood burning stove, a bookcase and a cedar chest. From the cedar chest emerged the highwall in question.

It was a coil spring model in 22 RF caliber, had been rebarreled by the owner, restocked with solid rosewood, had close coupled double set triggers and had been nicely reblued. A pretty nifty rifle but certainly not much for a collector. A little very loud haggling and the piece was mine. He was a tough negotiator and he wanted a pretty penny for the rifle but I figured I was probably supplying the winter’s cache, it being October, so I gave him the cash and he seemed satisfied. I really didn’t have any use for this gun but the trip and the cabin experience had to net me something, you know what I mean. Once home, I inspected the rifle carefully and found the gunsmithing, especially the rosewood stock work to be of excellent quality. The close coupled double set triggers worked perfectly.

Sometime shortly after this acquisition I was reading a Jack O’ Connor book and the thought of that old 30-40 Winchester sporter crossed my mind. Hey…that’s what I’ll do with that rifle.

Maybe at this point it’s a good idea to discuss a unique phenomenon peculiar to firearms’ aficionados. I’d call it “firearms fiscal insanity” or “FFI” for short. Let me explain. It all begins with the aforementioned dream rifle. Now that gun of yesteryear probably cost about $200 back in 1956 when I first saw it. I already paid way too much for the highwall I just bought and the cost of recreating that rifle of yore is certainly going to ring the cash register alot. It’s at this moment that the eyes glaze over, the price of the project rifle is immediately forgotten and only the image of the finished rifle blazes across the mind’s eye. All accounting skills are lost to lust and so it begins.

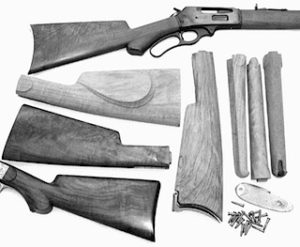

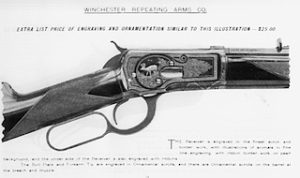

There is one fortunate thing about this problem, however, and that is the great length of time involved over the span of the entire project. At the completion of every phase of the project, the bill is received and blindly paid without regard for the amount, that blazing image still in command so to speak. And so it goes, polish and true up the action, lavishly engrave the frame, bend the lower tang to pistol grip, select the finest English walnut you can find, machine the stock set, fit, finish and checker stocks, blue and colorcase various parts, rebarrel, chamber, polish and rust blue, install engraved Dave Talley quick detachable 7/8″ mounts and rings [photo at right] , and finally find and  restore, to perfect condition, a Lyman Alaskan scope.

restore, to perfect condition, a Lyman Alaskan scope.

Eventually the project is complete, you saved none of the invoices, haven’t looked at cancelled checks and have the rifle of your dreams which probably cost you nearly 40 times the price of that old gun at Jaegers, but who cares. From out of the distant past has emerged that old beauty and who can put a price on it. This is “FFI”. All kidding aside, at some point in every gun lover’s career there comes a time to do something like this. After all, most us have owned nearly every factory rifle we ever wanted and now that unique personal touch is required to create the perfect rifle just for you.

In my case, there were a number of features that were important to me in the creation of this classic hunting rifle. I already had one of my favorite actions in the Winchester high wall and also the very desirable close coupled double set triggers. I’m really used to using these and can set and fire the rifle as naturally as anyone with a single trigger but I think I have the advantage of letting that shot off at just the right moment without disturbing my aim. It’s a great feature. Another important feature, to me at least, was the very handsome and utilitarian lines of the classic Winchester sporting stock.  These rifles just feel good in your hands and point about like a fine double shotgun. Poor eyesight necessitated the use of a scope on the rifle but Jack O’ Connor would have had a Lyman Alaskan and besides, these scopes were rugged and good looking on an “express” style hunting rifle.

These rifles just feel good in your hands and point about like a fine double shotgun. Poor eyesight necessitated the use of a scope on the rifle but Jack O’ Connor would have had a Lyman Alaskan and besides, these scopes were rugged and good looking on an “express” style hunting rifle.

We Exchange readers are a lucky bunch indeed when it comes to making our dreams come true. Paul Shuttleworth of CPA expertly rebarreled this rifle and had his master stockmaker fit, finish, and checker the beautiful English walnut stock  blanks [photo at right] from George Peterson of Treebone Carving. George has some exceptional wood and should always be considered on a project like this. The wonderfully detailed engraving was done by our friend Ken Hurst.

blanks [photo at right] from George Peterson of Treebone Carving. George has some exceptional wood and should always be considered on a project like this. The wonderfully detailed engraving was done by our friend Ken Hurst.

There is an interesting story behind the pattern I chose. Sometime back I remember seeing a fabulous engraved Pope Winchester highwall on the cover of John Grant’s book on Winchester single shots. I checked out the photo credits and found that Gary Quinlan owned this rifle. He generously had some very fine pictures made of the engraving on this rifle and I sent them to Ken asking if he could duplicate it. His response was that he couldn’t do quite as crude a job as the original. Okay, better is good.

There is an interesting story behind the pattern I chose. Sometime back I remember seeing a fabulous engraved Pope Winchester highwall on the cover of John Grant’s book on Winchester single shots. I checked out the photo credits and found that Gary Quinlan owned this rifle. He generously had some very fine pictures made of the engraving on this rifle and I sent them to Ken asking if he could duplicate it. His response was that he couldn’t do quite as crude a job as the original. Okay, better is good.

The pattern is nice because it depicts a running deer on the left side [photo at right] and a charging moose on the right [photo below]. The figures are extremely life-like and highly detailed. The heart shaped borders were not stamped, as was the original, but each has been hand engraved. Who knows how long this job must have taken but the results are spectacular.

To complete the package, the Talley rings were engraved with a matching pattern. The finish on  these late model Winchesters was a blued receiver and case colored block and lever. This work was done by Paul Shuttleworth’s blueing guy, Ron. By the way, Ron also has the original Winchester roll stamps for the high wall barrel and it was so marked, a nice touch, complete with the correct caliber marking of “.30 U S.”.

these late model Winchesters was a blued receiver and case colored block and lever. This work was done by Paul Shuttleworth’s blueing guy, Ron. By the way, Ron also has the original Winchester roll stamps for the high wall barrel and it was so marked, a nice touch, complete with the correct caliber marking of “.30 U S.”.

Although I’m a great fan of original rifles—any collector type is—somehow a tastefully done reconstruction like this is a fitting conclusion to an otherwise “ho-hum” piece. It was important to me that all the features incorporated in this rifle were actually available factory options when this rifle was new. Having the “Winchester Highly Finished Arms” catalogue was a great asset in completing this project. Some of the factory options available during the pinnacle of the single shot era were truly outstanding. Of course I would love to have paid the prices quoted in this catalogue for the work that was done, like full coverage engraving with gold or platinum inlays priced at $5 to $100, depending on coverage; fancy walnut was an extra $5 charge as was checkering.

A project like this requires attention to detail and good work doesn’t come cheap. I don’t think any country in the world has a larger number of firearms artisans than the United States, and for that we should be very grateful. Although this project ran into the years until complete, it was worth it.

A project like this requires attention to detail and good work doesn’t come cheap. I don’t think any country in the world has a larger number of firearms artisans than the United States, and for that we should be very grateful. Although this project ran into the years until complete, it was worth it.

Well, the old high wall is certainly an object of great beauty for sure, but will it shoot? I forgot to mention that I had the rifle barreled with a 26″ half octagon #3 Douglas barrel. This made the rifle weigh about eight pounds complete with scope. It’s fairly heavy, but around here the hunters “ambush” the deer from tree stands so walking miles into the woods was not a concern. The use of a fairly “stiff” barrel was also a consideration from an accuracy standpoint. I’ve owned many single shot rifles in modern high intensity calibers over the years and always took some heat from the bolt action guys about how those two-piece stock single shots would never shoot.

Back in the mid-60’s I built my first single shot rifle. I paid $5 for a large frame Peabody Martini action, fit a Douglas varmint weight barrel in cal .225 Winchester, stocked it with Fajen wood and parked a Unertl 15X Ultra Varmint scope on it. I killed a bunch of groundhogs with that rifle and even won a “Sporter Class” bench rest match with it. That match was a great “education” for the guys with the Remington 40 XB’s who shot against me. That old Martini shot a five-shot group that measured 338 thousandths of an inch, center to center, at 100 yards! Yeah, those two-piece stocks will never shoot.

Earlier I mentioned that the ballistics of the old 30-40 were or rather could be the equal of its 308 and 30-06 cousins. Originally loaded with the early cordite type powder and shooting a 220-grain  bullet at about 2100 FPS, the Krag quickly developed a reputation as the cartridge for moose, elk, bear and the like.

bullet at about 2100 FPS, the Krag quickly developed a reputation as the cartridge for moose, elk, bear and the like.

Today we have an abundance of .308 diameter slugs to choose from and with deer being the primary target the heavy 220 grainers seem a bit much. I decided to work up some loads with 150 grain and 180 grain bullets. The 180 grain slugs are Nosler AccuBond Spitzers boat tail and the 150 grainers are Sierra spitzer soft points. It always amazes me that most modern hunters are smitten with the magnum virus. Even around here, with the average shot being made at about 50 yards, the woods are full of 7mm Magnums. There are a few who do hunt the power line cuts and get to take advantage of the flatter shooting magnums, but for the most part, a good old 30-30 is just about all the gun you need.

I used to have a range on my property before the area got too built up and the annual deer season “sight in” usually brought the locals over to my place to see if their deer rifles were still sighted in from last year. Here I witnessed many cases of “magnum flinch” which usually resulted in offhand groups about the size of a spare tire. There’s an old adage that says, “Beware of the man who only shoots one gun, he usually knows how to use it”. To be sure, there is no substitute for practice with a rifle you are comfortable with. That’s one good thing about most of us single shot guys, we usually do a lot of shooting and our rifles have been carefully selected to provide optimum accuracy and ease of use.

This Winchester follows that course. The rifle is fairly heavy, has the double set triggers I am used to, and the 150 and 180 grain loads should be quite manageable in an eight-pound rifle. After studying the reloading manuals I quickly realized how “out of date” I was with many of the new propellants. I grew up in the era of surplus IMR powders when the hottest new stuff was Winchester  Ball C. I did note, however, that several loads were listed for powders like IMR 4350, 4831 and 4895. I had some experience with these, in fact my pet load for my .270 Winchester is 59.5 grains of 4831 behind the Sierrra 130 Gr boat tail spitzer. I like using these slow burning powders as they perform best with cases nearly full of powder. It’s pretty hard to overload a shell using this stuff. The 150 grain load suggested for the Krag round, in high strength actions only, was 50 grains of 4831. This load just barely leaves enough room to seat the bullet. The reported velocity was a little over 2600 FPS.

Ball C. I did note, however, that several loads were listed for powders like IMR 4350, 4831 and 4895. I had some experience with these, in fact my pet load for my .270 Winchester is 59.5 grains of 4831 behind the Sierrra 130 Gr boat tail spitzer. I like using these slow burning powders as they perform best with cases nearly full of powder. It’s pretty hard to overload a shell using this stuff. The 150 grain load suggested for the Krag round, in high strength actions only, was 50 grains of 4831. This load just barely leaves enough room to seat the bullet. The reported velocity was a little over 2600 FPS.

I loaded up a test round and fired it into the ground so I could inspect the fired case for any signs of excessive pressure. The case looked good, no cratered primer, no head bulge and easy extraction. Since I had equipped the rifle with what I considered the ultimate “heavy brush” scope, the Lyman Alaskan in 2.5 power, I shot the groups at 75 yards. When I had the scope refurbished by Gil Parsons of Parsons Optical Services, I had him install very heavy cross hairs. I guess they cover about four inches at 100 yards. This is not very conducive to shooting small groups at long range, but is pretty much ideal for what the rifle was intended to do. [Note: since the publication of this article, Gil passed away, August 28, 2010, and is sorely missed.]

After a few warm up and sight-in shots with this 150 grain bullet and 50 grains of 4831, I settled down to see just how this old timer would group. Using the ASSRA 100 yard target with a 3/4″ bull, the first five-shot group measured about 3/4″ at 75 yards. Recoil is  really quite mild but the muzzle flash using this old slow burning powder is spectacular! You would have thought I was firing a piece of artillery. I did find the heavy cross hairs a problem as they completely covered the white bull on the target. I guess it didn’t hurt too bad as the group was pretty good anyway.

really quite mild but the muzzle flash using this old slow burning powder is spectacular! You would have thought I was firing a piece of artillery. I did find the heavy cross hairs a problem as they completely covered the white bull on the target. I guess it didn’t hurt too bad as the group was pretty good anyway.

The Lyman scope was outstanding in that it was so bright. This rig would work really well in the dim light of early morning when most of the deer are shot. I must still be a kid at heart because I was excited to shoot the rifle and I could see my pulse moving the cross hairs. Realistically it was probably high blood pressure! Anyway, the set triggers came in handy in this regard as I could fire at the same point every time.

Next I tried some 180 grain Nosler AccuBond slugs in front of 37 grains of H 335 powder. Yeah, I know I said I was only going to use the old stick powders but, what the heck, I might as well give some of the new stuff a try. Recoil on this load was not really significantly different but the muzzle flash was not nearly so great. Point of impact shifted about 1/2″ lower but was still in line with the 150 grain bullet groups. A six-shot group measured about 1″ . Because I was in a hurry to work up  this article I didn’t fool around with different loads but just selected ones that were in the middle so to speak. From the results shown, it doesn’t look like there is much need for fooling around with these loads anyway.

this article I didn’t fool around with different loads but just selected ones that were in the middle so to speak. From the results shown, it doesn’t look like there is much need for fooling around with these loads anyway.

One thing I did notice during this session was that the rim thickness of the cases (Remingtons) seemed to vary quite a bit. Some of the cases were quite tight when closing the action. I’ve run into this with some of the new 45-70 brass as well. It seems odd to me that modern manufacturing practices can’t produce brass as uniform as they did 100 years ago. I will measure the rims of the fired cases and cull out the ones that are a little too thick next time.

So we’ve come full circle. Back in 1956, when I first saw a gun like this, I could only dream of ever owning one. This morning I got to fill my nostrils with that totally unique smell of smokeless powder, feel the recoil of a “meant for business” deer rifle and let my eyes play across the beautiful lines and colors of this wonderful rifle. Yes, Virginia, some dreams do come true.